“I was kind of moved to see our company is now traded as an AI-related stock.”

- Hisato Kozawa, CFO, Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, one of the “big three” global gas turbine manufacturers — following a brief dip in the company’s stock price when the launch of “DeepSeek” caused investors to question AI driven power demand

Egg prices received an inordinate amount of attention in the last election; and they continue to be a popular reference point for consumers worried about inflation. I personally care a lot about the price of eggs because I am an avowed “breakfast person”, and I have two hungry kids whose breakfasts are often partially spilled on the floor, or lost in the couch cushions, or fed to their stuffed animals.

But these days, I think we should all be paying much more attention to the price of electric power transformers.

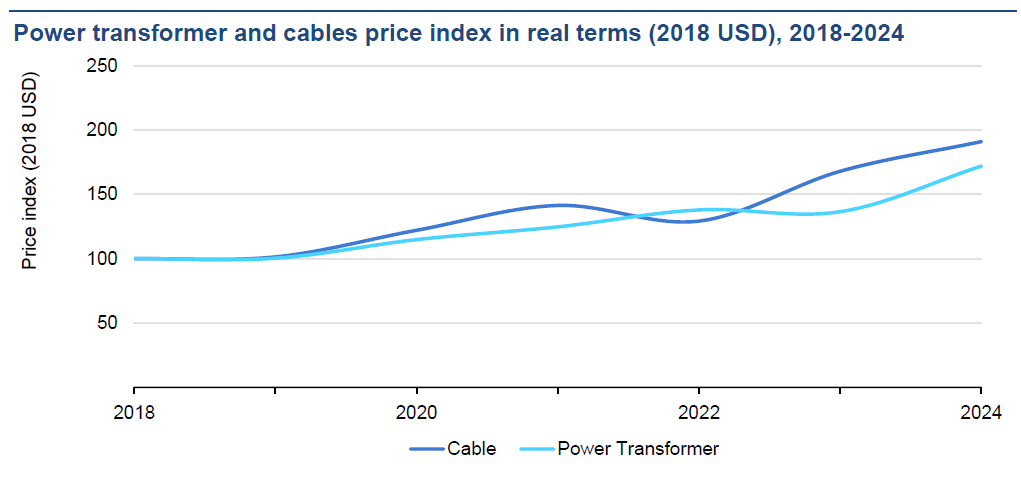

Last month, the IEA published a report with the results of a global survey on the cost of critical components for electric power grids. Here’s the money chart:

Real global prices for the two largest components of “the grid” have nearly doubled in the past five years. Initially, this new price regime was insigated by supply chain bottlenecks during the pandemic; but as the pandemic has receded, higher prices have not. Data from the US Federal Reserve tells a similar story, which applies to both transmission and distribution level equipment — including lesser-known, but nonetheless essential grid components like switchgear.

In addition to higher prices, buyers of power grid equipment are also facing much longer lead times. According to the US Department of Energy, lead times for transformers quadrupled from 2019 to 2023. Typical orders now take 1-3 years to fulfill. An industry working group found that 60% of utilities have had to delay or cancel projects of all kinds — ranging from residential service upgrades to data center interconnections — for want of a distribution transformer.

Unfortunately, there is no single fix for our transformer woes. There are bottlenecks up and down the supply chain.

Take grain oriented electrical steel, or GOES, which is the magical material at the core of a power transformer. The price of GOES, like the price of everything else, shot up during the pandemic and the inflationary period that followed. Yet unlike other important energy transition metals — like aluminum & copper — GOES is a niche material whose only major applications are in electrical equipment. Hence, the price of GOES is especially sensitive to the pace of global power grid expansion, so the GOES index has remained elevated while other metal prices have moderated.

The supply of GOES is particularly problematic here in the US, because there is only one, single domestic producer of the material. In fact, there is only one producer of electrical steel of any kind, here in America: a firm based in Cleveland, called Cleveland Cliffs.1

There are a variety of explanations for this state of affairs — including, in the US, uncertainty regarding DOE efficiency mandates and recently imposed tariffs — but the global story comes down to economic fundamentals. In short: demand for these products is simply rising much faster than supply. Electrification is accelerating, data center construction is booming, and global supply chains are strained. We’ve fully entered the Electricity Gauntlet which my colleagues and I began sounding the alarm about 18 months ago… and the world is not turning back.

That brings me back to the quote at the top of this post, and the final supply chain bottleneck which is keeping power system planners up at night: gas turbines. Since the pandemic, the price of turbines has escalated steadily, roughly in line with general inflation. But all signs now point to a much steeper price curve to come, as turbine suppliers are inundated with demand. The big three global gas turbine manufacturers — GE, Siemens, and Mitsubishi — are reportedly sold out through the end of the decade. Sonal Patel at Power Magazine recently captured a few more choice quotes from industry executives:

“We’re ramping up our capacity. We’re trying to produce more and more gas turbines. And frankly, we can’t make enough gas turbines to support this market.”

- Richard Voorberg, President, Siemens Energy North America

“I’ve been involved in the gas business for 12 years. I can’t think of a time that the gas business has had more fun than they’re having right now.”

- Scott Strazik, CEO, GE Vernova

Meanwhile, the price of renewable power has also risen substantially in many parts of the world — especially North America & Europe — in the past five years.

The causes of this phenomenon are manifold. Some are a direct result of the other bottlenecks I’ve been describing — for example, every renewable power project requires transformers and switchgear in order to connect to the grid. Other issues are specific to wind & solar. (For more context, see my prior post: “Adolescence For Renewables”). The result is that energy from new wind & solar projects is roughly twice as expensive as it was five years ago.

So your megawatts are getting more expensive…

I want to talk about two major consequences of a structurally higher electricity price environment.

1. Energy efficiency is becoming cool again.

Enthusiam for efficiency has historically come in waves, with the biggest surges (unsurprisingly) following the biggest energy price shocks. Famously, the first major wave in America was a result of the 1970s oil crisis — in fact, this was the period when the idea of “energy efficiency programs” led by utility companies originated. Many years later, when I was personally becoming interested in energy issues around 2005, oil and natural gas prices were once again spiking — and, no surprise, the concept of “negawatts” was beginning to be rediscovered.

But then came the Great Recession, the fracking revolution, and LED light bulbs — and consequently, “efficiency” returned to being a fairly boring topic for over a decade. Grander plans for efficiency investment were mostly stuffed into the broom closet.

Now that we seem to be headed for a structurally higher energy price regime, I’m already beginning to see some of those grand efficiency plans being dusted off. In a previous note on the frontier of heating and cooling technology, I’ve shared some of the investments we’ve made at EIP, like Transaera and Quilt. I’m also excited about our recent investment in Bedrock Energy, which is developing technology to dramatically lower the cost of drilling boreholes for ground-source heat pumps. In fact, there are signs of growth across the geothermal space. For example, the national home builder Lennar recently teamed up with the ground-source system provider Dandelion Energy to develop one of the largest residential ground-source deployments in history.

HVAC: the next frontier

Today’s charts come from two of our portfolio companies at Energy Impact Partners who have been hard at work building better systems for heating, ventilation, and air conditioning - aka HVAC.

2. Microgrids are finally having their moment.

“Microgrids” have been an intriguing concept for decades… but for decades, a concept is mostly all they’ve been. The idea sits right at the sweet spot where the interests of power system nerds, climate wonks, and national security hawks (and all sorts of “preppers”) overlap.

You know, people like this guy…

In very poor, rural, developing markets, a “microgrid” may be just what it sounds like: a very small grid — perhaps as small as a single generator and a few homes. But in developed markets like the US, the idea is usually to build a segment of the “macro” grid which is “islandable” during power outages, but still interoperable with the rest of the system during the 99.97% of the time when things are running smoothly. That segment might be as small as a single building, but it could also cover an entire college campus or industrial park.

Finally, after many years of nerds like me pining for microgrids, I’m finally seeing a real market opening in the US, Europe, and other developed countries. High costs and long lead times for centralized grid infrastructure are making large energy consumers take the idea of microgrids much more seriously. Consumers for whom access to power is especially urgent — e.g. data center developers racing to build and deploy AI models — have demonstrated a willingness to pay premium prices.

For AI, energy is nothing, and energy is everything

How serendipitous is it that data centers are measured in watts?

In this environment, microgrids are not just a way to accelerate time to power. They can also be the most affordable source of new capacity for the system as a whole. For example, our portfolio company Enchanted Rock has been a pioneer in deploying microgrids which are capable of supplying power to the grid for hundreds of hours a year (or more), while also offering their host customers an additional layer of resilience against sustained outages. We’re seeing an increasing number of electric utilites develop programs to deploy this kind of distributed generation as a means of serving new demand in a timely and cost-effective manner. Another of our portfolio companies, Sparkfund, is promoting an intriguing model called “Distributed Capacity Procurement”, in which utilities fully own and operate a variety of distributed generation and storage assets on customer sites.

They say necessity is the mother of invention…

But the fact is: we already have plenty of inventions in the areas I’ve highlighted above — energy efficiency and microgrid technology — to begin responding to constraints in the power grid supply chain. What we need is more rapid cycles of experimentation, validation, and deployment of that technology.

Fortunately, necessity is also beginning to accelerate those cycles.

In addition to Grain Oriented Electrical Steel (GOES), Cleveland Cliffs is also the only producer of Non-Oriented Electrical Steel (NOES).