Whether you prefer “energy dominance” or “net-zero” as a rallying cry, the need for revolutionary technology in the energy system has never been more clear. The electric power sector is at the vanguard, as surging demand from data centers has coincided with the emergence of supply bottlenecks at every level of the system. Last year, we described this state of affairs as an “electricity gauntlet” which the industry will probably spend the next three to four decades traversing. In the context of an energy system which took over a century to construct – with assets designed to last, in some cases, up to 80 years – we believe this situation presents an opportunity to build truly generational, revolutionary companies.

Of course, setting out to build any kind of revolutionary technology company is inherently a brazen act. The odds of success are low. This was true even for relatively capital-light software companies during the past thirty-year boom in “tech”, when billions of people connected to the internet for the first time, and then shortly thereafter began carrying a portal to the internet in their pockets. Now, the biggest winners from this era — e.g. Google, Microsoft, Amazon — already appear to be reaping the greatest gains from the next generation of AI technology which is being erected atop the edifice of the internet.

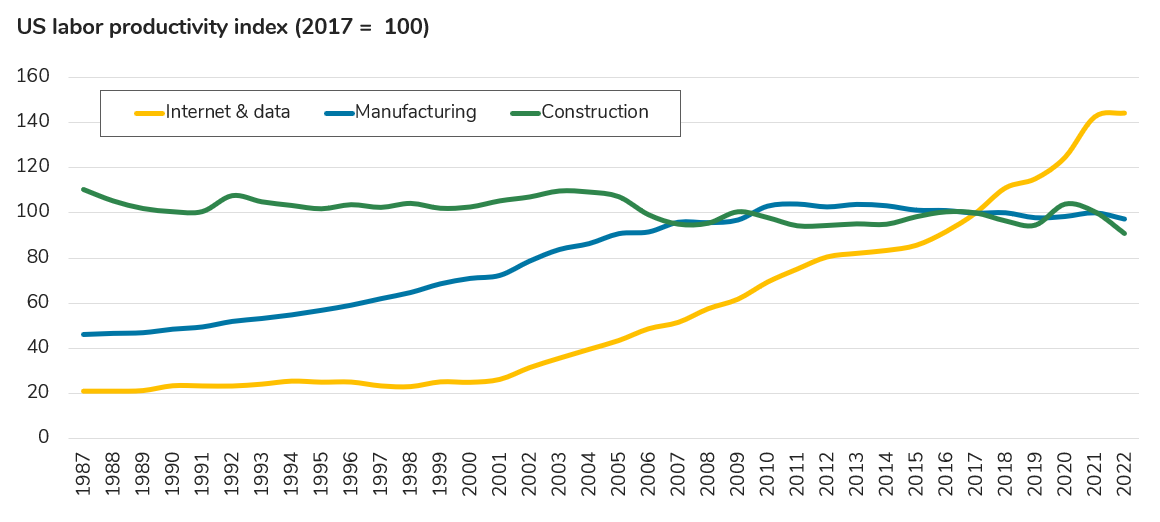

Internet technology has utterly transformed a handful of high-profile sectors – such as media, finance, and retail – which were easily conquered by software. Yet while labor productivity in these sectors has skyrocketed, productivity in sectors dominated by real, physical work has stagnated. It turns out that the more an industry is constrained by the stubborn, physical workings of molecules and electrons, the more difficult it is to disrupt with mere bits.

That brings us to the energy sector, in which the stubbornness of molecules and electrons is perhaps the most defining feature. We see five related reasons why it has proven especially difficult to build revolutionary companies in this sector.

Capital intensity is intense, because big physical systems nearly always cost a lot of money to build. Most venture capitalist are accustomed to writing checks in the millions or tens of millions. Large, first-of-a-kind projects often cost in the hundreds of millions – and occasionally billions.

Physics & chemistry are unforgiving, which makes research & development timelines long, and even more problematically, difficult to predict.

Products are mostly commodities, which means that green premiums are hard to come by. For most consumers, a kilowatt-hour is a kilowatt-hour. A ton of cement is a ton of cement. It’s notable that the most revolutionary success story in energy technology this century, by far, was Tesla — which was able to differentiate its products and command a sky-high brand premium from the beginning.

Reliability & security are paramount, which means that “moving fast & breaking things” is generally not an acceptable strategy.

The incumbent competition is fierce, as fossil fuels are astoundingly affordable, versatile, energy-dense resources… especially if you can burn them with the resulting carbon emissions unchecked.

We (Shayle and Andy) have spent our careers studying these challenges — including, for most of the past decade, at Energy Impact Partners. We’ve learned a lot, especially during the past five years since we launched our Frontier platform, which is purpose-built to invest in technology with truly revolutionary potential.

So, we thought we’d share some field notes.

The four T’s

Let’s start with the fundamentals: “the four T’s” for building any kind of revolutionary company, whether in the realm of consumer software, or the frontiers of electrochemistry. Team, TAM, Tech, and Timing.

This isn’t rocket science. Most early-stage investors recognize some version of these four variables as critical success factors. Yet, because of the distinctive challenges of the energy sector, we’ve found that getting the fundamentals just right is especially crucial. In a perfect world…

The founding team needs to be exceptional. Founders need to have all the traditional characteristics common to great leaders (grit, charisma, integrity), but experience is especially valuable here. The odds that a college student with a good idea is going to successfully navigate the treacherous maze ahead are extremely low.

The realistic TAM (total addressable market) needs to measure in the billions of dollars (at least). Given the scope and scale of the global energy system, there are plenty of markets measuring in the tens or hundreds of billions which are available to tackle.

The technology needs to be obviously better than the competition. 10-20% lower cost, or marginally superior performance won’t cut it. We usually look for at least 2X improvements over best-in-class alternatives, and 5-10X is preferable.

The timing needs to be spot on.

But, of course, we don’t live in a perfect world, and there’s no such thing as a company with a perfect score in all four of these areas. Hence, as an investor, it’s important to identify which of the four T’s are going to be the most critical for different kinds of endeavors. While every situation is unique, we’ve found that many of the aspiring revolutionary companies we encounter tend to fall into one of two broad classes; and these classes tend to diverge when it comes to their most important success factors.

Wave makers vs. riders

Imagine a technology revolution as a kind of tidal wave.

Sometimes these waves build gradually. They’re propelled forward by a myriad of secular trends which are not, in themselves, especially revolutionary. Demographic tides. Steady, incremental improvements in foundational technology building blocks. Consumer preferences. These kinds of forces occasionally coalesce into an unstoppable wave, and when they do, the best way to take advantage of that wave is usually to ride it.

Wave riders build the right solution, at the right time, to take advantage of a market opportunity just before a surge. Their products may be extremely novel and require “deep” technical research & development, but the key to success is getting a commercial product into the market at just the right time.

If you’re looking for a canonical example of a wave rider, look no further than Apple. In fact, just consider Apple’s most definitive product. The iPhone was propelled by some of the biggest waves of the 20th century: a premium market primed by Nokia and Blackberry; Moore’s law; the expansion of the internet; the rollout of cellular infrastructure; the growth of contract electronics manufacturing in China; liquid crystal display technology. We could go on and on. Apple didn’t initiate these waves, but the company surfed among them – churning them to higher & higher peaks, and steering them together into a mega-wave which was the mobile revolution.

You see, wave riders are by no means passive commuters on a macro tide. The best companies, like Apple, usually stir up the ocean into a much bigger and more powerful tsunami than they initially encounter.

On that note, there’s another class of company to discuss – one which doesn’t depend on incoming waves at all. These are the wave makers.

Wave makers set out to change the paradigm. They create products which very few people have probably considered before. (And those few who have contemplated the idea have probably rejected it, due to a variety of practical considerations.) In most cases, there are major gaps in the technology or business plan which the founding team will need to fill in, and there are no obvious solutions washing up in the tide. These are companies built through sheer force of creativity and drive. They bend the arc of the universe to their will.

One of the best examples of a wave maker also happens to be the most successful “energy transition” (or “climate tech”) company of the 20th century, so far. Of course, we’re referring to Tesla. When Tesla set out to build an electric vehicle, there were simply no waves on the horizon for the company to catch. Over a decade earlier, General Motors had briefly attempted to build an EV, and then abandoned the concept. There was even a documentary about this story, “Who Killed the Electric Car?”, released two years before Tesla shipped the first Roadster in 2008. So, there were no ‘precursor’ products, as in the case of the iPhone, to warm up or validate the market. Moreover, the key components of an electric vehicle were absurdly expensive. For the first Tesla Roadster, the battery alone cost over $50,000, and many analysts believed that lithium-ion batteries could never be produced cheaply enough for a mass-market vehicle. Lastly, there was zero public charging infrastructure, and nobody besides Tesla with an interest in building any. In short: Telsa had to create its own wave starting from completely still water.

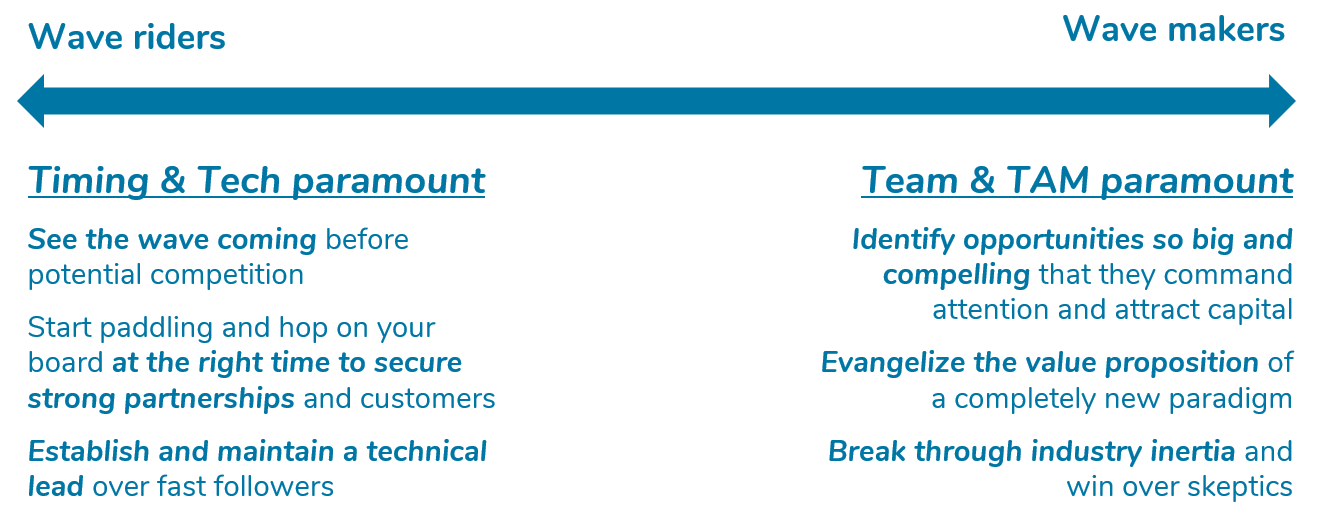

Of course, these two classes of company – wave riders and wave makers – are not entirely distinct. They exist along a spectrum, and most companies fall somewhere in the middle. Yet we’ve found that this basic dichotomy can still be a valuable tool as we assess investment opportunities, because it helps us consider which of the four T’s a company needs most in order to be successful.

For wave riders, we’ve found that timing and technology are paramount. Clearly it helps to see a wave approaching early, and begin to develop a product before your competitors. But it’s also important to carefully stage capital deployment, so as to avoid running low on cash too long before the wave you’re anticipating arrives. Hence, timing is a goldilocks problem, and the window between ‘too early’ and ‘too late’ is often surprisingly narrow. This is a major part of the reason why making rapid progress on technology is so crucial for wave riders. Because big waves attract competition, establishing and maintaining a technology lead is especially difficult... and vital.

For wave makers, we find that the strength of the founding team, and the scale of the addressable market, are the most important variables. Founders in wave-making companies often find themselves spending the majority of their time pitching an audacious vision. For years, their number one job will be to convince the right investors, staff, vendors, and partners to join them. Hence, these visions need to be sufficiently big and compelling to justify the risk of betting on a paradigm shift; and founders need to be especially charismatic and credible in order to win hearts & minds.

Some examples from the EIP Frontier portfolio

Wave riders:

Transaera is an air conditioning technology company riding two waves. The first is obvious, and global: the world is getting warmer, and richer. And the places where both population growth and economic development are occuring most rapidly — i.e. Southern Asia — are getting warmer & richer especially quickly. One of the most well established laws of behavioral economics is that as people in hot places enter the “middle class” (globally speaking), one of their first purchases is an air conditioner.

The second wave Transaera is riding is less apparent at surface level. It’s in the field of materials science, in which an extremely versatile class of materials called “Metal Organic Frameworks” (or “MOFs”) is gaining momentum. The company’s core innovation is in the application of a particular breed of MOF — which happens to be highly efficient at capturing moisture from the air — in order to create an air conditioning solution which is heads and tails more efficient than incumbent competition. Their first product is a drop in replacement for conventional, dedicated outdoor air handling systems.

Ceibo has developed a fundamentally better technology for extracting copper from low-grade sulfide ores, which make up ~70% of the world’s known copper reserves. The wave at play here is the looming shortfall in copper production relative to demand, a wave that the entire industry sees coming and struggles to overcome because of the challenges and timelines inherent in developing new copper mines. Instead of relying on that multi-decade process, Ceibo can plug into operating mines, increasing output and avoiding the need to build expensive, hard-to-permit concentration & floatation units. Ceibo is now benefiting from a second emerging wave of deglobalization, as their technology avoids the need to ship copper concentrate to China for smelting.

Wave makers:

Form Energy builds multi-day batteries. That category simply did not exist prior to Form, and largely does not exist in the absence of Form. The company is indeed riding the tailwinds of increasing intermittent generation, rapid load growth driving grid capacity constraints, and increasing incidence of extreme, multi-day weather events. But even with those trends firmly entrenched, Form has needed to create, define, and quantify the value of a new category of asset on the grid — and in so doing, conjure its own market.

Of course, this process began with Form honing in on a novel battery chemistry which has a fundamentally different cost entitlement than any battery in use today. But less plainly, it has also required the company to build a new set of analytical tools which can help grid planners determine exactly when and where such an unfamiliar type of asset will be most cost-effective. This pursuit led Form to build up a world-class power system analytics team, in addition to its physical science & engineering teams. The result is a set of tools that are valuable, in their own right, for utility planners — and capable of producing compelling thought leadership which plants the seeds for the physical product. Here’s an example from a recent paper published in collaboration with Charles River Associates.

Koloma is a geologic hydrogen exploration company. The concept of geologic hydrogen (vast natural stores of underground H2 formed by water-rock interactions, just waiting to be extracted as the first new source of primary energy since nuclear fission) was largely an academic backwater when Koloma was founded. Today, thanks in part to Koloma’s paving of the path, there is a worldwide hunt underway for the Permian of H2.

Of course, there are also plenty of hybrids — companies which embody elements of both wave makers and riders. We’ll probably discuss some examples in future posts.

Here’s to making, and riding, transformational waves!

I completely disagree with the idea that Tesla was a wave maker instead of a wave rider.

The concept of electric vehicles was not new when Tesla emerged. Hybrids were gaining traction in the 2000s, and the Nissan Leaf was released before the Tesla Roadster. Additionally, e-bikes were becoming popular in Asia. Tesla's innovation was not in the idea itself but in its execution. Elon Musk's genius was in hiring an awesome designer, Franz von Holzhausen, and creating hype around the brand.

Tesla primarily rode the wave of falling costs of lithium-ion batteries, driven by manufacturers in Asia. Musk did, however, create a significant wave with the successful development of reusable rockets through SpaceX.