Steel for Fuel, Tariffs for Steel

Tariffs on steel are a tax on nearly every form of energy production and distribution

The name of this blog, “Steel For Fuel”, is a reference to the basic exchange which defines the energy transition: replacing fossil fuel combustion with big, steel structures — e.g. wind turbine towers, solar piles, and nuclear reactor vessels.1 Actually, “Stuff For Fuel” is an even better tagline, because the energy transition is reliant on all kinds of other mineral resources besides steel — e.g. copper, aluminum, nickel, neodymium, etc.

But today I want to focus on steel, because steel has been in the news. Specifically, tariffs on steel have been in the news. Well, actually, all sorts of tariffs have been in the news, some of which have even more obvious impacts on the building blocks of the energy transition than steel. Solar and batteries, for example, and high-power electric motors dependent on rare earth elements. I’m sure I’ll return to these topics in a future post.

But I want to focus on steel, because steel tariffs are a good example of how President Trump’s topsy-turvy tariff regime is already beginning to impact the energy sector. Some impacts are fairly simple and direct; but others take a number of macroeconomic twists and turns. In the end, we may be surprised to find that clean energy is not so disproportionately burdened as meets the eye…

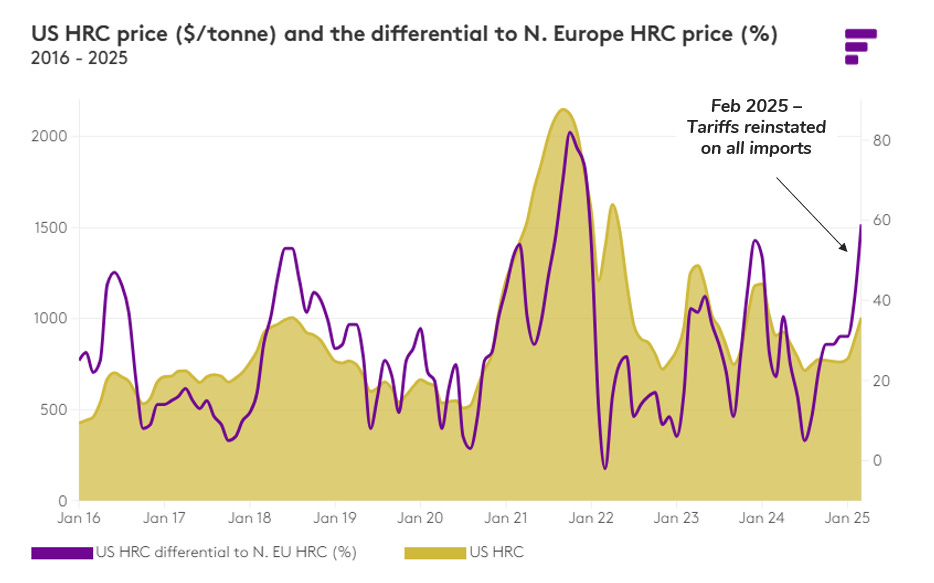

Where to begin? In the United States, steel imports have been subject to a 25% tariff since President Trump’s first term, in 2018. However, many countries were granted exemptions from this tariff until just recently, when the President reinstated the measure, with no exceptions, in February.2

Global steel prices are fairly volatile to begin with, so the impact of tariffs is not immediately apparent in historical market data. However, it’s possible to observe some signal in the noise. For decades, American steel prices have been persistently higher than those in other regions. But since the Trump tariffs were first imposed in 2018, prices in the US have been especially sensitive to tight supply & demand conditions — periodically spiking well above the global average. And since steel tariff coverage was expanded in February, the price differential between the US and other regions rose to its highest level since the covid supply chain crunch. (See the chart below on the US versus the next highest priced region, Northern Europe, from Fastmarkets.)

These steel market dynamics are especially important for renewable power, because — as I highlighted above — wind & solar use a lot more steel than other forms of power generation. (The same is true for aluminum, and copper, and many other minerals.) With American steel prices surging to their highest levels since the covid crunch, the cost of steel alone now amounts to nearly 10% of the capex of a typical US wind project, and roughly 5% in the case of solar.3

Those costs would be meaningfully lower if US steel prices were closer to those in Europe or Asia.

Of course, the price of steel matters for all sorts of other energy infrastructure, too. Electric transmission lines are made of aluminum conductors reinforced with over half a ton of steel per mile, strung between massive towers weighing in at a whopping 40-60 tons of steel each. Electric transformers depend on a highly specialized steel alloy called “grain oriented electrical steel” with only a single US supplier. Hence, higher steel prices are already contributing to the rising cost of power grid capacity, which I discussed in a recent post.

The price of power grids

“I was kind of moved to see our company is now traded as an AI-related stock.”

And yet, despite these obvious risks to the pace of clean energy deployment, steel tariffs may end up having an even greater impact on the price of fossil fuel.

The price of steel is not particularly important to the total cost of a natural gas power plant (as the chart above illustrates). However, steel prices are most certainly important for the price of oil & natural gas. Steel pipes make up about 10% of the total cost of a new well, and an even higher share of the cost of the pipelines which are needed to connect new wells to existing infrastructure. According to Patrick Rao, an analyst at Natural Gas Intelligence, steel makes up roughly a third of the cost of new gas pipeline projects.

Moreover, natural gas may be even more exposed to the ripple effects of a burgeoning trade war and macroeconomic downturn. More than a third of American gas supply is “associated gas” which comes from wells drilled primarily for oil. Hence, if trade conflict causes a global recession, which in turn causes oil prices to fall just as tariffs are increasing the cost of American oil production, then American natural gas production could also suffer as a result. Yet even during a recession, I think the odds are pretty good that we see continued growth in global demand for natural gas, driven by sustained global investment in power generation to serve data centers, along with electric vehicles, electric heat pumps, and air conditioning.

Hence, we may be entering a period in which global gas demand is rising, while supply from American wells is depressed. That’s a pretty obvious recipe for higher prices. In this scenario, it’s entirely possible that steel tariffs will actually end up making new renewables more competitive, on the margin, with gas generation.

In sum: It’s easy to see why steel tariffs will lead to increased costs for clean energy infrastructure, because so much of it is built upon big, steel structures. But steel is also a critical input to natural gas production, and gas may be even more exposed to the macroeconomic effects of global trade conflict than renewables.

So ultimately, all I can say with confidence is that steel tariffs will make electricity more expensive. Nuts.

More to come in future posts on “Silicon Wafers for Fuel”, “Rare Earths for Fuel”, Etc.

Credit to Xcel Energy, which coined the phrase to describe a major investment in wind power across its territory in the upper Midwest, Colorado, New Mexico, and Texas.

Countries which had received exemptions from Trump’s 2018 steel tariffs were: Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Japan, Mexico, South Korea, the European Union, Ukraine, and the United Kingdom.

Based on a steel price of $1,000 per ton for “hot rolled coil”, as of March 2025.