Last year, I concluded a series of Ten Big Questions on the future of energy and climate technology. From the start, I hinted at an even more momentous bonus question.

So, here goes.

Will geopolitics derail the energy transition?

As our last President was fond of saying, “Here’s the deal”: At this point in history, the biggest risk to the energy transition is excessive conflict between the US and China.

The word “excessive” in that statement is doing a lot of work. These countries don’t need to adore each other. They don’t need to agree on political philosophy, or who controls every nook and cranny of the South China Sea. I have no doubt that some amount of conflict between these two countries is unavoidable in the coming decades. Global superpowers tend to be wary of each other, and the US has woken up to the fact that China is now undeniably a superpower — having surpassed the US economically, technologically, and militarily in a number of critical areas. Meanwhile, from China’s perspective, America probably still seems like a proverbial 800-pound gorilla, constantly beating its chest and threatening to suppress the ambitions of rising powers.

So, I fully anticipate more intense economic conflict between the US and China. But we can’t go to war. I hope it goes without saying that truly “kinetic” conflict would be very, very, very bad. If it comes to World War III, we’ll all have much bigger problems than decarbonization, for a very long time to come. (Also, if it comes to World War III, I’m not convinced that my own country, America, would win. If you’re not already frightened about this, please go read Noah Smith.)

Still, there are also plenty of risks from geopolitical & economic volleys back and forth which fall short of an outright war. Fundamentally, global cooperation is crucial for the energy transition because no country can afford to decarbonize unilaterally. I wish it weren’t so, but it’s undeniable that the energy transition will consume a lot of capital and make some aspects of life more expensive — especially in the industrial sphere. That’s what it means to internalize an externality — sorry. And neither the US, nor China, nor any other major country can afford to cede too much industrial capacity, which is crucial as both a source of economic strength and as a deterrent against aggression.

And so the board is set. Let’s consider the players.

The (clean energy) manufacturing superpower

China is now frequently described as the world’s first “clean energy superpower”. This title is undeniably apt, as Chinese supply chains have become indispensable for the two most important building blocks of the energy transition: solar photovoltaics and lithium-ion batteries. Raw materials for these goods are sourced all over the world: Australia, Chile, and Indonesia… as well as China. But nearly every step in these supply chains beyond mining is heavily concentrated in China — from refining, to intermediate process steps, to final products.

And yet, the title of “clean energy superpower” actually belies China’s more foundational superpower, which underpins its supremacy in solar, batteries, and all kinds of other industries: unmatched excellence in manufacturing.

Pick a chart covering nearly any trend in global manufacturing from the past quarter century (since the US normalized trade relations with China). They all tell pretty much the same story: China has taken over global production.

Now, for some heavy construction materials, like steel & cement, these trendlines don’t necessarily reflect the country’s manufacturing prowess; they just reflect the combination of its massive population and rapid industrialization. As China became richer beginning in the 1990’s, the nation sensibly funneled that wealth into building a tremendous amount of new homes, schools, office towers, roads, power plants, etc. It’s not surprising that a massive country whose share of global GDP nearly quintupled — with much of that growth fueled by infrastructure investment rather than consumption — has built a lot of steel & cement plants.

But of course, it’s not just domestic commodity production that makes China a manufacturing superpower. China has earned its nickname, “the workshop of the world”, by steadily mastering the production an increasingly complex array of goods. In the process, the country has ended up with an unparalleled manufacturing ecosystem comprised of massive hubs which span factory floors and process engineering: Shanghai, Shenzhen, Guangzhou, Ningbo… the list goes on. This ecosystem has now become a daunting competitive moat — some might say an unassailable one. In the words of Apple CEO Tim Cook, all the way back in 2017:

“The popular conception is that companies come to China because of low labor cost. I'm not sure what part of China they go to, but the truth is China stopped being the low-labor-cost country many years ago. And that is not the reason to come to China from a supply point of view. The reason is because of the skill, and the quantity of skill in one location and the type of skill it is...The products we do require really advanced tooling, and the precision that you have to have, the tooling and working with the materials that we do are state of the art. And the tooling skill is very deep here.”

“In the U.S., you could have a meeting of tooling engineers and I'm not sure we could fill the room. In China, you could fill multiple football fields.”

The result has been a positive feedback loop for manufacturing capacity & innovation… and of course, for Chinese exports.

A few notes on this story…

Chinese exports are no longer just the kinds of low-margin consumer goods that many Americans and Europeans still associate with “Chinese manufacturing” — e.g. cheap toys and electronics, or even really nice electronics, like iPhones. Today, Chinese exports also include affordable, high-quality electric vehicles. In fact, they include all kinds of vehicles, as China has rocketed into position as the world’s leading exporter of all kinds of passenger vehicles (per Dunne Insights).

Relatedly, China now has more than 80% global market share of commercial electronic drones, whose surprisingly high value as combat assets has recently been demonstrated on the battlefields of Ukraine. The nation is now leveraging its dominance in global battery manufacturing to undercut international drone competitors, like US-based Skydio.

China is the world leader, by a mile, in the adoption of industrial robotics. Regular Steel For Fuel readers will know that this makes me very jealous.

China is also very good at AI. In case you’ve been hiding under a rock: A few weeks ago, a little-known Chinese private equity firm released an open-source model called DeepSeek which appears to be following the well established tech paradigm of “America invents, China optimizes”.

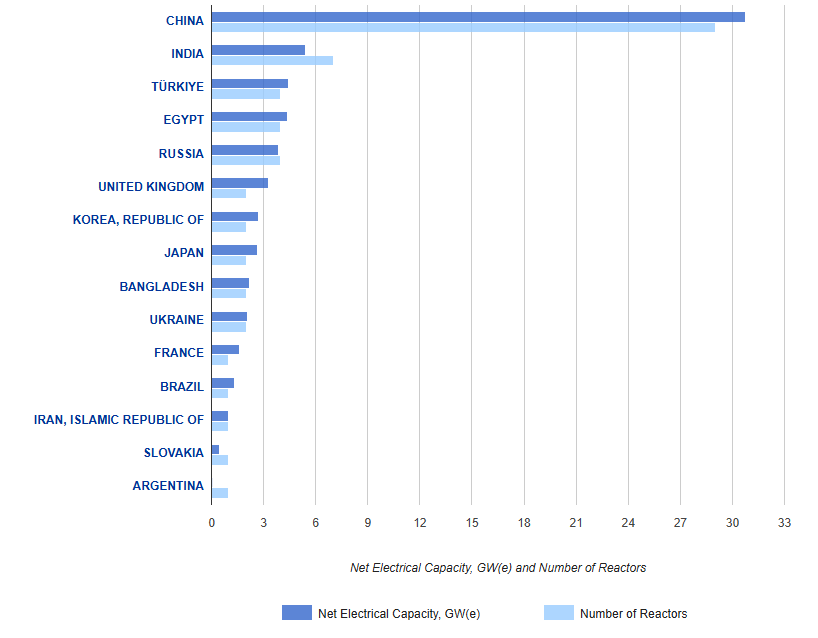

In addition to its dominance in solar & battery manufacturing, China has also become a rising leader in another critical decarbonization solution: nuclear power. In the past decade, China more than doubled its installed reactor capacity; and now has nearly as many reactors under construction as all other countries combined! (The chart below, from the International Atomic Energy Agency, tracks reactors being built across the world.) Currently, many of these reactors are sourced from Western suppliers — e.g. the Westinghouse AP-1000 — however, China’s “Belt and Road” program calls for exporting at least thirty of their own, home-grown reactors by 2030.

There is one very important caveat to any discussion about China’s manufacturing superpowers — especially in the realm of clean energy: Most of China’s manufacturing might is still powered by coal.1 China is one of the few countries still adding an enormous amount of new coal-fired power generation. In fact, China is building so much new coal-fired generation that the rest of the world’s coal additions have become, effectively, a rounding error. Frankly, China still deserves the title of “coal superpower” much more than it deserves to be called a “clean energy superpower”. Manufacturing practically anything in China remains substantially “dirtier” in nearly every respect — including greenhouse gas emissions — than manufacturing in America. Moreover, China’s continued reliance on coal to fuel its manufacturing boom will have repercussions for global carbon emissions for many decades to come. Consider: The average coal-fired power plant in the US is 43 years old, while the average coal-fired power plant in China is 13…

China’s persistent investment in coal power is a good reminder that clean energy is just one small element of a much more comprehensive industrial strategy — and it’s a strategy which is decidedly not geared towards near-term climate change mitigation. For decades, the government has taken very deliberate steps to build up manufacturing capacity across a wide range of strategically relevant sectors. And Beijing now appears to be doubling down on this strategy, as a recent bust in the country’s real estate market has led the government to redirect low-interest loans from state-controlled banks from property developers to manufacturers. Although analysts at Rhodium Group and Bloomberg have questioned the efficacy of this approach, the government’s intent seems very clear.

On the other hand, I don’t want to downplay the growing importance of solar & batteries within the scheme of China’s overall industrial policy. Both technologies received an especially big stimulus from Beijing’s most recent push. Just as the US and Europe were beginning to push back against Chinese dominance with their own manufacturing incentives, tariffs, and restrictions on Chinese imports (given credible accusastions of forced labor in Xinjiang province), Beijing’s latest push appears to have given rise to an historically unprecedented surplus of manufacturing capacity which threatens to overwhelm the global market.

The same is true for batteries.

It’s impossible to miss the link between this aggressive investment in renewables and China’s long-term security. China has a dearth of liquid hydrocarbons, and its access to oil & gas imports depend on a relatively small number of critical global choke points. Specifically, the Straight of Malaca is the world’s biggest naval choke point for global oil supply, and China is the biggest buyer of oil which passes through the Straight of Malaca.

In this context, it’s not entirely surprising that China has forged a strategic partnership with Russia, which recently found itself in need of new markets for oil & gas exports following its ruinous invasion of Ukraine.

It’s also not very surprising that China has prioritized developing alternative primary energy resources, and electrifying non-military vehicles, as a strategic security imperative.

That brings us, in a roundabout way, to the United States…

The hydrocarbon superpower

In stark contrast to China, the US has become an unmatched hydrocarbon superpower — the world’s #1 producer of both oil and natural gas for several years running. Our ample fossil fuel reserves, continent-spanning network of pipelines, and extraordinarily resourceful oil & gas industry have grown into a tremendous source of global competitiveness & security. In recent years, we’ve increasingly wielded these resources as a an instrument of global influence, most notably, by scaffolding Europe through its painful breakup with Russia — and redirecting exports of liquefied natural gas (LNG) from elsewhere in the world.

The US was able to do this in part because there is some flexibility in the global market for liquified natural gas, or LNG, but also because we’re an LNG behemoth — not just the world’s largest producer, but also the world’s largest exporter. As I wrote in “The US is a natural gas superpower”, for context:

“Last year (2023) US exports of LNG contained about five times as much energy as all of the solar energy generated in the country.”2

And we’re on track to double LNG export capacity by the end of the decade.

Every indicator suggests that the Trump administration aims to double down on America’s strengths as a hydrocarbon producer. Trump is also doubling down on tariffs, which the Biden administration already raised materially on Chinese solar & battery exports, towards the end of last year. (Biden’s tariffs also targeted several countries in Southeast Asia, and extended to key solar photovoltaic inputs, such as polysilicon and wafers.)

Even more concerning than the direct impact of these tariffs is the threat of retaliation from China. Given China’s grip on the critical minerals required to manufacture solar panels, batteries, and electric vehicle motors, Beijing has the power to choke aspiring producers anywhere else in the world. Just in the past year, China has exercised this power by restricting exports of graphite and rare earth minerals. This kind of activity puts dozens of shiny, new, domestic US solar and battery cell manufacturing plants at risk.

Hence, as the US prepares to invest in an even more robust supply of hydrocarbons, our energy transition supply chains are becoming even more exposed.

What about everyone else in the world?

I’m told there are other countries besides the US and China…

So how will these other countries react to the growing divergence between the world’s superpowers on the future of energy and climate?

Being an American, I’m afraid to say that this divergence probably puts China in a stronger long-term geopolitical position relative to the US. While American hydrocarbon exports are currently crucial for our longtime allies in Europe and East Asia, both of those regions are much more aligned with China on a multi-decade vision for decarbonization of the global economy.

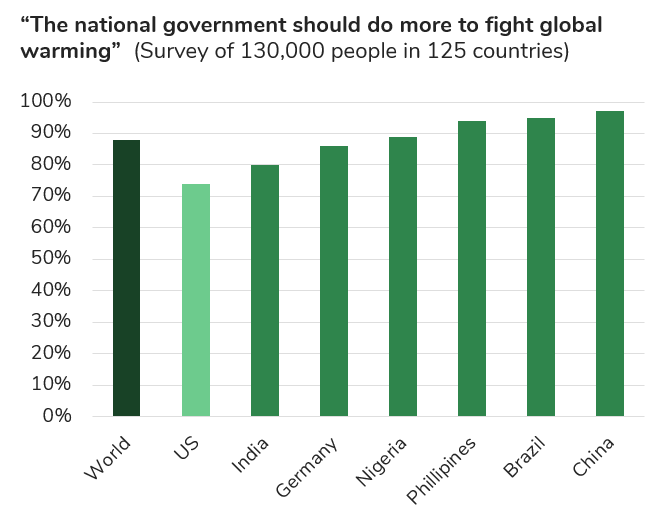

In a massive global survey of public attitudes towards climate policy, Chinese citizens were among the most favorable towards more government action. The US is increasingly an outlier at the low end of the spectrum, drifting away from the public in many large countries with burgeoning populations — e.g. Brazil, Philippines and Nigeria.

And the US political “right”, which is currently in power, has become even more of a global outlier. On the topic of climate, Europe’s conservatives now appear closer to the US “left” than they are to the average Republican. I want to emphasize that this is not just my personal assessment of the situation, based on my own observations and political preferences. This dynamic is backed up by solid public opinion research.

To be clear: public preferences, as revealed by survey data, are by no means a perfect predictor of a nation’s policy choices. This is especially true in less democratic societies, like China. (On the other hand, I wish I could say public opinion translated more efficiently into policy here in the US…) In any case, I find that this kind of data can be valuable as a directional indicator of the public’s response to various policy choices. And in this case, given the choice of greater dependence on American hydrocarbons or Chinese solar panels & batteries… I believe that the weight of public opinion will increasingly favor solar & batteries, over time.

Of course, climate is just one of many dimensions of this choice, and it’s definitely not the most important dimension for the majority of the public in most countries. Security and economic vitality tend to come first. Yet, climate has absolutely become a salient issue now for many governments, and I expect that we’ll see China’s strengths in this domain steadily increase the country’s geopolitical leverage.

In fact, the rest of the world already seems to be turning toward China when it comes to some of the most important elements of the global energy system.

Take vehicle electrification, for example. China is by far the global leader in EV adoption among major economies, but Europe may be catching up. This year, the market share of passenger EVs in Europe is poised to grow even faster than in China, according to the market research firm S&P Global. And while the rest of the world still lags in electric four-wheel passenger vehicle adoption, other major segments of the global market are moving much faster. See, for example, “three-wheeler” vehicles in India:

Now that the floodgates on Chinese vehicle exports have opened, and we’re seeing offerings like BYD’s $10,000 fully electric Seagull enter global markets, there is even more reason to anticipate accelerated adoption in the rest of the world.

Call it the beginnings of “Seagull Diplomacy”?

“Solar Diplomacy” may also become more commonplace in emerging markets. Look at Pakistan, for example. Given rising electricity prices and an unreliable power grid, rooftop solar adoption in the country is taking off. According to Bloomberg, Pakistan imported 13 GW of solar panels from China in just the first 6 months of 2024 — which is an extraordinary amount for a country with just 50 GW of existing power generation. Meanwhile, as declining grid consumption threatens to worsen the government’s fiscal position, Pakistan is reportedly “renegotiating with Chinese and domestic investors over power-sector debts and exploring ways to privatize certain companies”.

Stabilize the globe, stabilize the energy transition

My fear is that this divergence in superpowers will result in energy & climate playing more of a central role in the evolving schism between the US and China.

As an American, I’m concerned that China’s superpowers will put the country in a better position to influence global events, over time. But I’m not just worried about America’s standing in the world. I’m also worried about a globe increasingly carved into an American economic sphere founded on hydrocarbons, and a Chinese economic sphere much more interested in advancing renewable power. This would certainly slow down the energy transition here in America — which is still a major source of global emissions — and would probably slow down the energy transition everywhere.

So, my question is: What can we do to mitigate this risk? What would it take to make decarbonization a force that stabilizes and binds the world together, rather than yet another wedge in a burgeoning great power conflict?

I have a few ideas which you might even call a “six-part plan”. These are all pretty focused on my home country, because that’s the place I know best. Fortunately, I think these are the kinds of ideas that ought to be able to garner bipartisan support. A few of them are clearly emerging as big priorities for the Trump administration.

Try to avoid an actual war. (Duh.)

Build up an independent North American supply chain for solar, batteries, and electric vehicles. This… will take some doing. It will require a delicate balance of protectionism (yes, tariffs), government incentives, and almost certainy some new technology to overcome the enormous lead in both industry knowledge and scale which China has amassed. There may be a chance for North America to leapfrog China with radically new technology which avoids most of the Chinese solar & battery supply chains. For example, at my firm Energy Impact Partners, we’ve invested in 6K, which has developed a much more sustainable, lower cost technology for manufacturing battery electrode materials. Speaking of materials, I think there might be a step change possible for solar, as well. (Cough, perovskites, cough.) I’m also excited about solutions focused on critical minerals circularity. For example, EIP has also invested in Cyclic Materials, a rare earth minerals recycling company which I believe could be a game changer for the security of the rare earth magnet supply chain in America and other Western nations.

Make America great — at nuclear — again. The United States invented nuclear power, led the world in deployment in the 60’s and 70’s… and then stopped. But, thanks to the knowledgeable nuclear workforce sustained by our large installed base of nuclear power plants, our nuclear navy, and our world-leading research institutions, we’re not so badly positioned to pick back up where we left off. The US has a fighting chance to lead the world in nuclear technology and construction optimization, once more. “It’s time to build (light water reactors)!”

Lead the world in carbon capture and sequestration. We’re a fossil fuel superpower, and we have some of the world’s best geology for sequestering carbon dioxide underground, for goodness sakes. Plus, nobody in the world is doing CCS all that well today, so there’s a real opportunity to establish a global leadership position. That said, we need to make sure that any early technical edge we develop is not snatched away — as it was in the case of solar photovoltaics and lithium-ion batteries — by other countries that scale up deployment faster. Hence, CCS leadership can’t be confined to startup labs. It needs to take the form of real projects. It’s possible that if we do this right, even China could become a major customer for American CCS technology in 10-20 years, when the nation finally decides to confront the carbon emissions from all of the new coal-fired power plants they’ve been building. (If you want to learn more about CCS, check out my last post on the topic, below.)

Will CCS make a lot of these other questions moot?

Current hypothesis: Nope. But it could be a regionally important solution.

Push the boundaries in manufacturing & construction automation. The only way the US will truly be able to compete with China — and just as crucially, the world’s new low-cost labor centers in Southeast Asia — is to reboot progress on labor productivity in these sectors. Fortunately, I believe we’re seeing the beginnings of an inflection point in robotics. In our own portfolio at EIP, for example, we’ve invested in Infravision, a robotic system for stringing electric transmission lines more safely and affordably. (For more on robots, check out my previous piece “From SaaS to Robots”.

Make it easier to permit and build all this stuff. Where have all the transmission lines gone? The same place that so many other kinds of big infrastructure projects have gone to die: your friendly, local (or state, or federal) permitting department. It’s not just a feeling: proverbial “red tape” at nearly all levels of government is holding back nearly all kinds of projects across America, along with many other advanced democracies. I’m crossing my fingers that this can be an area for bipartisan compromise in the very near future. It does seem to be a major priority for the Trump administration, which has declared our inability to build energy infrastructure a “National Emergency”.

I wish I could have trimmed this down to a three-part plan, which I’m convinced is the best package for selling the public anything approaching a policy platform. But, I’m sorry to say that six parts is the right number. Am I convinced that implementing all six pillars would avert the worst risks of geopolitical conflict? Sadly, no. But for the sake of the climate (not to mention world peace) we ought to give it a try.

Want to read more “Tales of Two Things"?

If so, check out my prior post: “A Tale of Two Nanettes”. I promise it’s much more lighthearted than this one. It’s about my grandmother, my daughter, and timelines.

A Tale of Two Nanettes

[Note: This post is adapted from a keynote presentation I gave at the Energy Impact Partners annual meeting in May 2023.]

Coal, with carbon emissions entirely unabated.

~12 bcf/day of LNG = 1,270 TWh of embodied energy per year. US solar power generation totaled 238 TWh in 2023.