The US government is pumping the brakes on electric vehicle policy. (Get it?)

EV subsidies appear to be doomed. This has led to some fairly alarmist headlines…

In addition (and probably more importantly) the Trump administration has revoked California’s ability to set its own vehicle emissions standards under the Clean Air Act. Those standards would have required automakers to steadily increase their sales of “zero-emissions vehicles” in the state, on a timeline which, frankly, even many longtime EV believers like me considered aggressive. This executive action also applies to the sixteen other states, plus Washington D.C., which had also adopted more stringent requirements under the same waiver from federal standards as California.1 Ten of those states have joined California in a lawsuit challlenging the administration.

Clearly, these are not positive developments for the pace of EV adoption in America.

And yet, I find myself even more confident in the EV revolution — even here in America — than I was before Nov 5th, 2024. The revolution here will probably not be subsidized, or mandated. It will almost certainly be slower than in most other countries. But I’m convinced that it cannot be stopped, because battery electric drivetrains are simply a superior technology. Even if you set climate aside, I believe they have what it takes to win on the merits; and there are more reasons to believe so today than there were before the November election.

So, for those of you who are feeling glum about these headlines, I want to highlight three positive trends in the global EV industry which have accelerated since the US government changed hands — all of which, I believe, are more important than the vicissitudes of federal policy.

I. The dream of a mass market vehicle with 300+ miles of range and 5 minute charging is now a reality (in China).

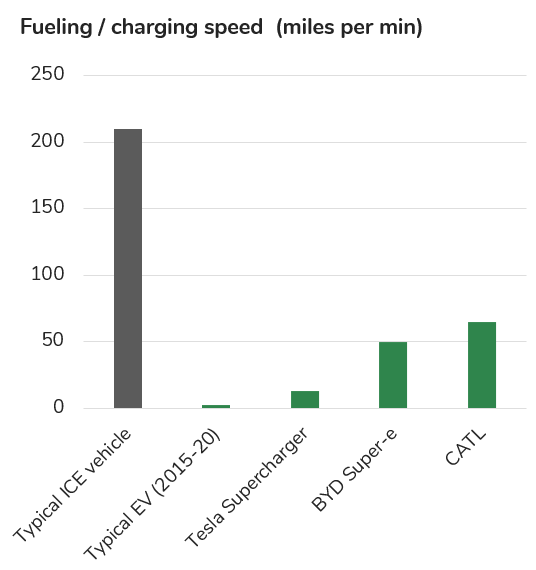

China has quickly become the world’s leading passenger vehicle exporter for a reason: The country produces high-quality vehicles for shockingly low prices, especially in the electric segment (which makes up about a third of its exports). In March of this year, BYD announced a new EV platform called “Super-e”, which employs a new 1,000 Volt architecture to enable truly ultra-fast charging. These vehicles are reportedly capable of adding 250 miles of driving range in 5 minutes. The base model, the Han L, has a full battery range of 370 miles, and will sell for just $29,000.

Not to be outdone, China’s other big battery champion CATL announced an even faster-charging battery just one month later!

These charging speeds are still about 3-4 times slower than the flow of liquid hydrocarbons into an ICE vehicle. However, they are now close enough to remove practically all of the excess friction from the charging experience, compared with refueling at a pump.

In the words of Tu Le, Managing Director of Sino Auto Insights:

“If I can add 250 miles in five minutes, what does this mean for oil and gas?”

In my view, these advances effectively shift the full burden of “range anxiety” — that perennial boogeyman of the EV market — from the inside of a vehicle to the outside. There are now just two remaining hurdles to making passenger EVs preferable in nearly every way to their ICE equivalents: 1) Geopolitical barriers to technology diffusion; and 2) Energy infrastructure barriers to fast-charging deployment. (This is the hardest part.)

That brings me to the second positive development for EVs…

II. American EV manufacturing is making great progress, actually.

A little over two years ago, I pointed out that geopolitical tension between the US and China was the biggest remaining risk factor to the global success of EVs. (I reiterated this point more recently in “A tale of two energy superpowers”.) I’m sorry to say that China has since widened its lead at practically every step in the EV supply chain. BYD’s lead, in particular, may now be insurmountable.

However, this doesn’t mean that America can’t have really nice, affordable EVs.

We may be behind, but there are still signs of life in the US supply chain. While partnerships with Chinese manufacturers appear to be off the table, American OEMs are working even more closely with Japanese and Korean suppliers — particularly LG Energy Solutions. And technology has a way of spreading across even the toughest geopolitical terrain…

For example:

In March, Hyundai opened America’s largest factory dedicated to EV and hybrid vehicle production, in rural Georgia. The company calls this enormous campus — which includes a $4 billion battery manufacturing joint venture with LG Energy — a “Metaplant”. It’s now one of the most highly automated plants in the country, with more than one “robot” for every two human workers. This kind of industrial automation has become one of China’s strong suits, and there is no way that America is going to achieve similarly low cost, high-quality EV production without matching or exceeding China in pursuit of radical labor productivity. (See: "An Ode to Physical AI”.)

In May, General Motors and LG Energy announced a partnership on an emerging class of battery cells which might be able to compete head-to-head with Lithium-Iron Phosphate (LFP) technology, which is still heavily controlled by the Chinese giants.2 This new “Lithium-Manganese-Rich” (LMR) chemistry purportedly dispenses with most of the expensive nickel (and cobalt) cathode materials which have historically been necessary for higher-density cells. GM and LG are boasting that they can achieve LFP costs with about 30% higher density, and are planning to commence giga-scale production in 2028. Personally, I’ve learned to be extremely skeptical that anyone can pull ahead of Chinese LFP; but even if this announcement is a bit overconfident, this is still a very welcome development.

Speaking of LFP and LG Energy… America now has its first major domestic LFP gigafactory.

At an aggregate level, investment in US battery manufacturing is down slightly from its peak in Q4 of last year. But it’s still pretty darn robust. The Rhodium Group has still tracked $10.4 billion in Q1 investment in 2025.

Admittedly, we’ve also seen some companies cancelling projects. However, as Julian Spector of Canary Media has pointed out:

“T1 Energy, Kore Power, and Our Next Energy share something in common: They are venture capital-backed startups attempting to compete with the incumbents of the global battery industry. That model hasn’t produced a standout success yet — even Tesla initially tapped an incumbent, Panasonic, to make EV batteries at its Nevada Gigafactory.”

Battery cell production has proven to be one of the most exacting domains in all of advanced manufacturing. (Semiconductors are probably the only products that are tougher to get right.) At this point, we’ve all learned that this is not a promising domain for startups… and that’s okay! Partnerships between auto OEMs and leading incumbents will do just fine.

III. Autonomy is real now, and autonomy favors the electron.

Autonomy is moving extremely quickly. Just a few months ago, I published a post called “Autonomy is real now”, and that already sounds like a timid understatement. In that piece, I pointed out that autonomous vehicles have a natural affinity for electric drivetrains. I’m convinced that the confluence of these trends will be a major driver of EV adoption moving forward. Quoting myself:

“One subtle point that tends to fly below the radar (LiDAR?) in this type of analysis is that autonomy is very favorable for electric vehicles. In fact, Waymo’s entire fleet is already electric, and I strongly doubt this is merely a case of corporate altruism.

Autonomous vehicles are generally going to be high-utilization vehicles. That’s true because they can be, but also because they need to be in order to justify such high capex. This is an ideal scenario for the electric drivetrain, which has lower maintenance and lower energy costs than the internal combustion engine.1 The more a vehicle is utilized, the more these operational advantages matter when it comes to the total cost of ownership. Additionally, all of those expensive sensors and chips which need to be packed into an AV also need to be powered, which compounds the efficiency advantage of going electric. It’s just silly to contemplate running 13 cameras, 4 LiDAR units, 6 radar units and multiple GPUs on an internal combustion engine.”

In sum: The EV revolution is probably not going to be subsidized here in America. That may be a drag on the market in the next few years. But take heart, friends: EV technology is looking more attractive than ever. The revolution can’t be stopped, even here in the U.S.A.

Autonomy is real now

“We tend to overestimate the effect of a technology in the short run and underestimate the effect in the long run.” - Amara’s law

These states (+ D.C.) were acting under the same waiver granted to California.

BYD and CATL are the runaway global leaders in LFP technology & manufacturing.

Surprising and welcome data for Q1 investment!